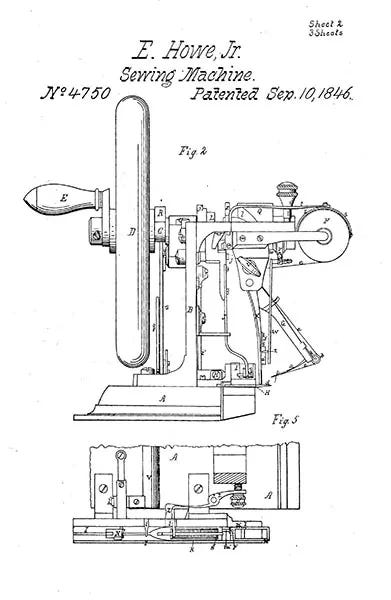

This Day in Legal History: Howe Sewing Machine Patented

On this day in legal history, September 10, 1846, Elias Howe was granted U.S. Patent No. 3640 for his revolutionary sewing machine. Howe’s invention was a significant breakthrough, speeding up the process of garment production and forever changing the textile industry. However, Howe's legal battles soon followed, as other inventors, including Isaac Singer, began producing sewing machines that closely resembled Howe's patented design.

In 1854, Howe sued Singer, accusing him of patent infringement. The court ruled in Howe’s favor, affirming that Singer’s machine did indeed infringe upon Howe's patent. This victory not only solidified Howe’s place as the rightful inventor of the sewing machine but also secured him substantial royalties from Singer's machines, which were gaining widespread popularity.

The case marked an important moment in patent law, demonstrating the power of legal protections for inventors during the Industrial Revolution. By enforcing his patent rights, Howe reaped financial benefits and ensured that his invention would be recognized for its originality.

In a significant victory for the European Union's regulatory efforts, Apple and Google both lost high-stakes court battles related to antitrust and tax issues. The EU’s Court of Justice upheld a €13 billion ($14.4 billion) tax ruling against Apple, finding that Ireland’s favorable tax treatment of the company amounted to illegal state aid. Apple had previously condemned the 2016 decision, but the court’s ruling now forces Ireland to determine how to handle the recovered taxes.

In a separate case, Google lost its challenge against a €2.4 billion fine for leveraging its dominance in search to prioritize its own shopping services over competitors, a ruling that reinforces the EU’s efforts to regulate Big Tech. These decisions mark a major success for Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s antitrust chief, as she prepares to leave her position after spearheading years of regulatory scrutiny on tech giants, including Amazon and Fiat.

Both Apple and Google expressed disappointment with the rulings, but the decisions signal a continued regulatory clampdown on Big Tech in Europe, bolstered by new legislation such as the Digital Markets Act, which aims to prevent companies from favoring their own services over rivals. The rulings set a global precedent, as other regulators around the world increasingly scrutinize Silicon Valley’s market dominance.

Apple Loses EU Top Court Fight Over €13 Billion Irish Tax Bill

In the start of the Google antitrust trial, the U.S. Department of Justice argued that Google used its size and power to dominate the online advertising market, accusing the company of monopolistic practices. During the opening of the trial in Alexandria, Virginia, prosecutors claimed that Google controlled both sides of the ad tech ecosystem by eliminating competition, acquiring rivals, and locking in customers. Google's actions allegedly stifled competition in a market handling over 150,000 ad sales every second.

Google’s attorney, Karen Dunn, dismissed the case as outdated, comparing it to relics like BlackBerrys and iPods. She argued that Google's tools now work alongside competitors and that the digital ad market has shifted, with major players like Amazon and Comcast providing significant competition. Google’s defense echoes its arguments in a recent search monopoly case, which it won.

The Justice Department seeks a ruling that could force Google to divest key ad tech products like Google Ad Manager. The trial will continue for several weeks before a ruling is issued by U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema. This case is one of several recent efforts to challenge Big Tech monopolies, with similar cases against Meta, Amazon, and Apple also underway.

Google aimed to control web ad tech, US prosecutor says as trial begins | Reuters

In a piece I wrote for Forbes—and with apologies for the double dose of me today—I delve into the tax loophole used by the ultra-wealthy known as the "buy/borrow/die" strategy. This tactic allows the wealthy to use highly appreciated assets as collateral for loans, giving them access to large sums of money without triggering taxable events. While some propose taxing loans at disbursement, I argue that a better approach would be a "repayment realization" rule, where taxes are applied when these loans are repaid, aligning more closely with traditional tax principles.

Taxing at disbursement could open the door to various tax avoidance strategies, such as using offshore lending or taking out smaller loans to stay under tax thresholds. Additionally, taxing loans at the time of issuance could complicate valuations of illiquid or hard-to-value assets, making enforcement difficult. A repayment realization rule, on the other hand, would ensure that taxes are triggered when wealth is actually monetized to repay the loan, addressing these loopholes.

This approach would also reduce the risk of manipulation through rolling over loans or making small repayments, as each repayment would be taxed proportionally. While there are challenges, like preventing double taxation, this proposal offers a more effective solution to ensure the ultra-wealthy pay their fair share of taxes when they access their wealth.

Closing The Loan-Tax Loophole: Considering “Repayment Realization”

In my column this week for Bloomberg, I propose the creation of an IRS-managed "encyclopedia of tax fraud" to help taxpayers spot scams early. While some fraudulent schemes are so obvious they’re easy to recognize, others are packaged cleverly as legitimate tax strategies, making it difficult for the average person to tell the difference. Although the IRS publishes resources like the "Dirty Dozen" list of frauds, these are often too technical or hard to locate, limiting their usefulness.

I suggest a Wikipedia-style online database, maintained by the IRS, that offers clear, plain-language explanations of fraud schemes, real-life examples, and the warning signs people should look for when receiving tax advice. This would allow taxpayers to identify potential scams before becoming victims or unwittingly participating in fraud. It would also explain the consequences of engaging in fraudulent activity, serving as a deterrent.

By compiling this information in one place, the IRS could better protect taxpayers and safeguard vital tax revenue, making the job of scam artists much more difficult. My aim is to create a first line of defense for taxpayers as fraud schemes become increasingly sophisticated.

‘Encyclopedia of Fraud’ Would Help Taxpayers Spot Scams Early