This Day in Legal History: Free Speech at the Movies

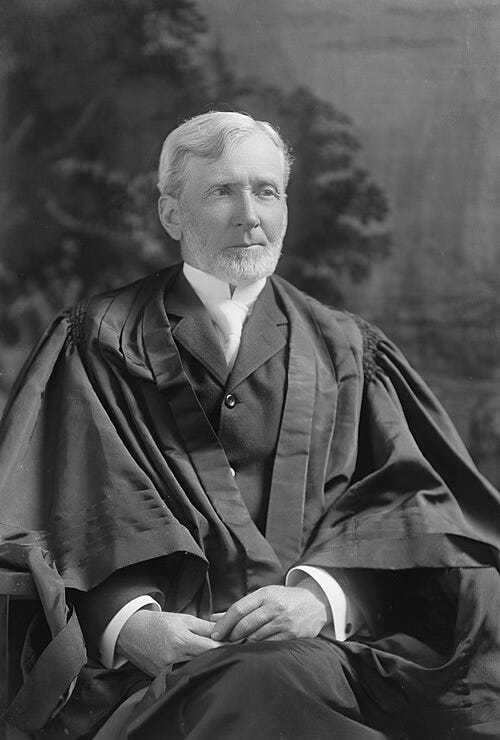

On this day in legal history, November 25, 1915, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, holding that motion pictures were not protected under the First Amendment. The case arose when Ohio enacted a law requiring films to be approved by a censorship board before public exhibition. Mutual Film Corporation challenged the statute, arguing it infringed upon free speech and press freedoms. The Supreme Court unanimously rejected that argument, declaring that movies were a business enterprise, not a medium of public expression deserving constitutional protection. The Court emphasized that films could be used for evil and lacked the inherent public value of newspapers or books.

This ruling gave states and cities wide discretion to censor films, leading to the rise of local and state censorship boards that controlled what audiences could legally view. It also provided a legal foundation for the Motion Picture Production Code, or Hays Code, a system of industry self-censorship that dominated Hollywood for decades. For nearly 40 years, this decision limited the creative scope of filmmakers and allowed governments to suppress films based on moral, religious, or political grounds.

It wasn’t until Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson in 1952 that the Supreme Court reversed course, striking down New York’s ban on a film deemed “sacrilegious” and recognizing movies as a significant medium for the communication of ideas. The reversal marked a turning point for First Amendment jurisprudence and artistic freedom. But on November 25, 1915, the legal system closed the door on film as protected speech—setting the stage for a long legal battle over cinema’s place in American constitutional law.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s misconduct complaint against U.S. District Judge Ana Reyes was dismissed. The rare complaint accused Reyes of bias in her handling of a case challenging President Donald Trump’s ban on transgender individuals serving in the military. Chief U.S. Circuit Judge Sri Srinivasan ruled in September that judicial misconduct proceedings were not the proper venue to raise such concerns, suggesting instead that the DOJ could have filed for Reyes’ recusal if it believed she was unfit to preside.

The complaint, filed in February before Reyes ruled on the case, alleged she had shown hostility during hearings by expressing disbelief, questioning a lawyer’s religion, and engaging in behavior the DOJ claimed compromised the dignity of the courtroom. The Justice Department claimed her conduct showed potential bias. In March, Reyes blocked Trump’s executive order, though her ruling is currently on hold pending appeal. The complaint was one of only two such filings by the DOJ amid broader tensions between Trump’s administration and the judiciary. Neither Reyes nor the DOJ commented on the dismissal.

US DOJ’s misconduct complaint against judge in transgender military ban case gets tossed | Reuters

A federal judge dismissed the criminal cases against former FBI Director James Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James after finding that the prosecutor who brought the charges lacked lawful authority. The judge concluded that Lindsey Halligan, appointed by the Trump administration as interim U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, was installed in violation of the Constitution’s Appointments Clause and federal law governing interim U.S. attorney appointments. Because her appointment was invalid, every step she took—including securing indictments—was deemed an unlawful exercise of executive power and therefore had to be vacated. The judge rejected the Justice Department’s argument that the attorney general could repeatedly make interim appointments without Senate confirmation, noting that doing so would sidestep the constitutionally required process. Attempts by Attorney General Pam Bondi to retroactively validate Halligan’s actions—such as re-appointing her as a special attorney and “ratifying” the indictments—were also found ineffective.

Under the Appointments Clause of the U.S. Constitution and federal statute, U.S. Attorneys must be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. When a vacancy arises, the Attorney General may make an interim appointment, but that appointment is limited by law to 120 days. If a permanent U.S. Attorney is not confirmed within that time, the district court may appoint a replacement to serve until the vacancy is officially filled. This process is designed to ensure both accountability and separation of powers, preventing the executive branch from indefinitely bypassing Senate oversight by cycling through temporary appointments. Repeated or back-to-back interim appointments without Senate confirmation undermine this framework, raising constitutional concerns about legitimacy and legality.

The cases were dismissed without prejudice, leaving the door open to new prosecutions, though the expired statute of limitations appears to bar refiling against Comey. Defense lawyers had additionally characterized the charges as politically driven, but the court did not need to reach those claims because the appointment defect alone required dismissal. The ruling underscores that prosecutions must be brought by properly appointed officials, and that structural constitutional violations invalidate downstream actions—even in high-profile or politically charged cases.

US judge tosses cases against ex-FBI chief Comey, New York AG James | Reuters

A federal judge has denied Arkansas health worker Joy Gray’s request for immediate reinstatement after she was fired over social media comments made following the murder of conservative figure Charlie Kirk. Gray sought a preliminary injunction requiring the Arkansas Department of Health to rehire her, continue paying her, or provide a “name-clearing hearing” to protect her reputation. However, U.S. District Judge Lee P. Rudofsky ruled that Gray failed to demonstrate the kind of irreparable harm necessary to justify emergency relief, emphasizing that job loss—even from a government position—does not automatically meet that legal standard. He cited controlling precedent, noting Gray did not show she couldn’t be adequately compensated by monetary damages if she ultimately wins her case.

The judge also rejected her claim that the department’s actions were currently chilling her speech, pointing out that the firing was a past event and not part of an ongoing restriction. Additionally, her request for a name-clearing hearing was unlikely to succeed, as the court found no stigmatizing statements in the department’s response. Rudofsky was careful to clarify that this ruling does not determine the outcome of Gray’s broader First Amendment retaliation claim, which may involve more complex legal questions as the case proceeds.

State Worker Fired for Kirk Posts Can’t Revive Job During Trial