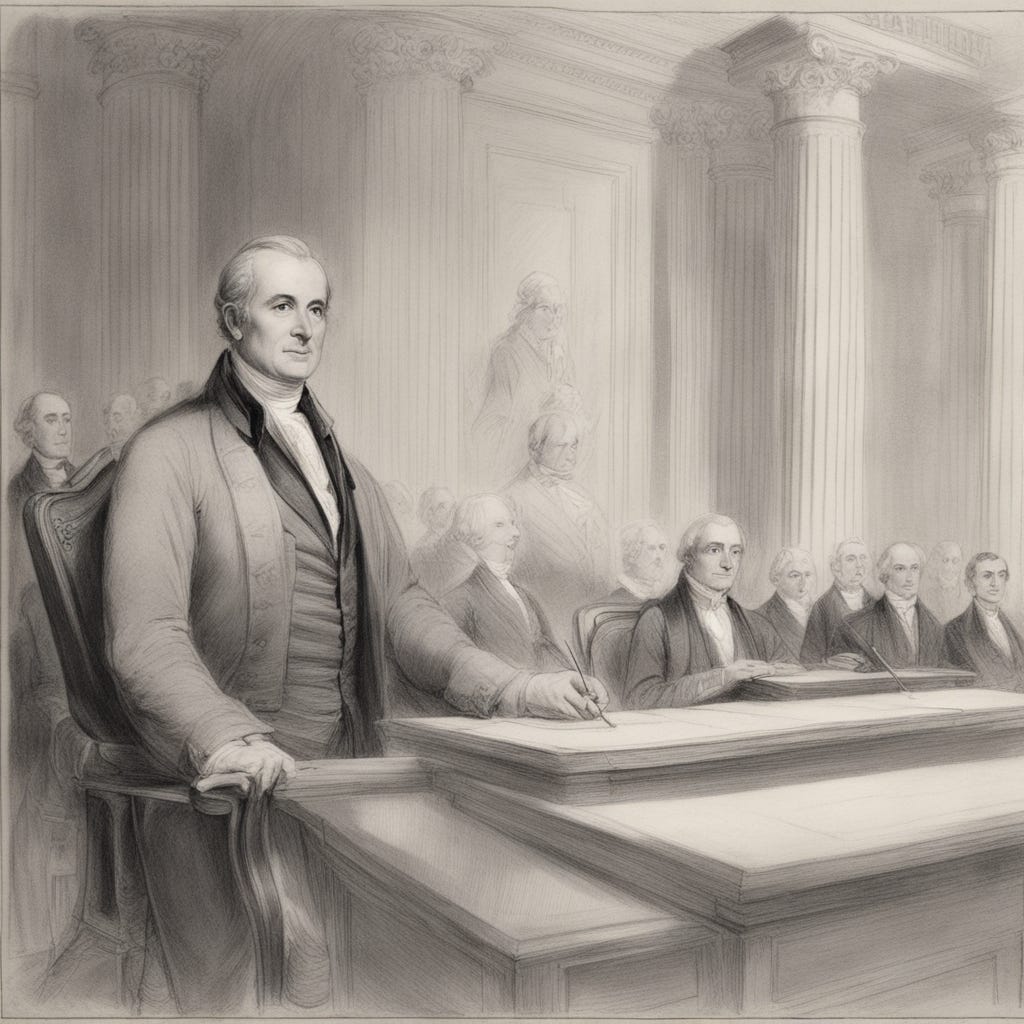

On this day in legal history, September 26, 1789, John Jay was made the first Chief Justice of the United States after the Senate confirmed his nomination.

On this day, September 26, we commemorate a cornerstone moment for the American judicial system: the passing of the Judiciary Act of 1789. Signed by President George Washington, this landmark legislation established the Supreme Court of the United States, laying down the legal framework that would ultimately make it the most significant judicial body in the world. The Judiciary Act provided for a Supreme Court comprised of six justices, and on that very day, Washington nominated John Jay as the first Chief Justice, along with John Rutledge, William Cushing, John Blair, Robert Harrison, and James Wilson as associate justices. The U.S. Senate wasted no time in confirming all six appointments.

While the U.S. Supreme Court was originally established by Article 3 of the U.S. Constitution, the Judiciary Act of 1789 fleshed out the high court's practical structure and functions. It granted the Court ultimate jurisdiction over all laws, especially those challenging their constitutionality. Additionally, the Court was tasked with handling cases involving treaties, foreign diplomats, and maritime law. The first session of the Court took place on February 1, 1790, in New York City’s Royal Exchange Building, further cementing its role in American governance.

Over the years, the Supreme Court has evolved both in structure and influence. While the number of justices fluctuated during the 19th century, Congress stabilized it at nine justices in 1869—a number that can still be altered by legislative action. Today, the Court stands as a pivotal institution in American society, often playing a decisive role in resolving pressing issues, especially during times of constitutional crisis. Thus, the events of September 26, 1789, mark not just the inception of the Supreme Court, but the beginning of a judicial institution critical to the shaping of American democracy.

Stefan Passantino, a former lawyer for the Trump White House, has filed a defamation lawsuit against Andrew Weissmann, a former special counsel prosecutor. The lawsuit alleges that Weissmann falsely claimed that Passantino had improperly coached his client, Cassidy Hutchinson, a former White House aide, to lie in her testimony to the House Jan. 6 committee. Passantino denies having done so, labeling the accusation as an "insidious lie" in the legal complaint. The lawsuit was filed in the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., and asks for a jury award of an unspecified amount exceeding $75,000.

This is not Passantino's first legal action related to the Jan. 6 probe. In April, he filed a similar lawsuit against the House committee, stating that members had also spread false information about him. The issue revolves around Cassidy Hutchinson's claim to the committee that Passantino advised her to say she couldn't recall specific details about an incident involving former President Donald Trump on January 6.

After Hutchinson's testimony became public, Passantino's law firm, Michael Best & Friedrich, severed its relationship with him. Additionally, a group called Lawyers Defending Democracy filed a complaint to have Passantino's law license revoked over his counsel to Hutchinson. Passantino alleges that Weissmann's actions were driven by "partisan animus" and resulted in "injurious falsehood" against him. He also claims that a statement from Weissmann, made on September 15, has significantly damaged his professional reputation and caused financial losses. As of the reporting date, Weissmann has not responded to requests for comment.

Ex-Trump Lawyer Passantino Sues Weissmann, Alleging Defamation

In the world of private equity, a phenomenon called "zombie funds" has emerged, characterized by aging firms unable to raise new capital and struggling to exit old investments. This issue has been highlighted by the case of Fenway Partners, once a booming company, now reduced to a three-man team with a lingering investment in a helmet-making company beset by lawsuits. Industry-wide, there's been a decline in new fundraising, partly due to rising interest rates and partly because pension funds have maxed out their allocations to the illiquid asset class of private equity. As a result, many older funds are finding it increasingly hard to liquidate their existing assets.

Public pension funds across the U.S. are particularly stuck with such zombie funds. These include funds managed by First Reserve, an energy-sector specialist, and Yucaipa Cos, a money manager led by supermarket mogul and Democratic donor Ron Burkle. Analysts warn that when private equity firms don't raise new funds, it leads to the gradual loss of staff, leaving only a skeleton crew to manage remaining assets, which in turn deteriorates fund performance. This creates a dilemma for investors, as exiting these problematic funds typically means incurring steep discounts.

Pensions and endowments can't easily exit these funds, nor replace the managers unless there is evidence of wrongdoing. Reports from 10 major public retirement systems show that they have a median 4% of their private equity portfolios locked up in funds older than 2009, amounting to around $6.8 billion across more than 900 fund investments. These often-underperforming investments can remain stuck for years, eroding returns and tying up valuable managerial time.

The first wave of zombie funds emerged after the 2008 financial crisis. Now, a new wave is taking shape as pension funds are steering less cash into private equity, especially towards smaller, untested firms or those with tarnished histories. The phenomenon represents a stark counterpoint to the promise that private equity can offer reliable, long-term returns. The situation is worsened by slowdowns in the mergers and acquisitions and IPO markets, making asset sales more difficult. Therefore, while some funds may survive in a weakened state, others could face dramatic derailment, leaving investors with limited options and less-than-ideal outcomes.

Wave of Zombies Is Rising From Private Equity’s Slow Carnage (1)

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is considering a significant overhaul of federal credit reporting rules under the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970. The changes could bring additional companies, including data brokers not currently covered, under these rules. Among the proposals is a potential ban on the use of medical debt in consumers' credit reports. The CFPB is also concerned about "credit header data" and may limit when such data can be sold for use by various entities like lenders and law enforcement.

The proposed changes would also require major credit reporting companies like Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion to improve their data security measures and overhaul how they handle consumer disputes. They may need to investigate systemic issues based on consumer complaints and notify those affected. Legal disputes are also being revisited; the current bifurcation between legal and factual disputes may be amended to ensure consumer protections.

The outline of the proposal was submitted to a small business review panel, and only after their review will a full proposal be developed. The changes are expected to have a far-reaching impact on all businesses involved in consumer data, according to law firms and consumer advocates. Critics argue that some proposals might exceed the CFPB’s legal authority, particularly as the agency has faced legal setbacks in federal courts.

It's worth noting that the CFPB has focused its outline mainly on the impact of these changes on small businesses, leaving room for potentially even more extensive changes that would mainly affect large credit reporting companies. The formal rule, once issued, is expected to face legal challenges. Both supporters and critics of the proposal agree that the language in the existing credit reporting law might be broad enough to make these significant changes legal, but the agency's recent losses in court cases could create hurdles.

CFPB Eyes Broad Expansion of Federal Credit Reporting Standards

The IRS's new rules, detailed in Notice 2023-63, clarify the definition of software development for tax purposes and require most related expenses to be amortized over time rather than expensed in the current year. This change poses significant challenges for bootstrap software developers—startups that lack typical streams of venture capital and often rely on expensing software development costs immediately. Prior to 2022, Section 174 of the tax code allowed businesses to expense research and development costs in the year they were incurred, which was especially beneficial for startups and small developers.

Another issue arising from the new rules is the administrative burden of distinguishing between what constitutes "maintenance activities" and what is considered an "upgrade or enhancement." While maintenance activities are exceptions to the amortization requirement, the definitions are not clear-cut, leading to complications for developers and potential legal disputes.

The new tax rules create ambiguity that could discourage innovation by making software acquisition less burdensome than software development from a tax standpoint. Developers have expressed disappointment that recent changes in tax law, specifically the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), did not revert to allowing current-year expensing or provide a narrower definition of "software development."

In my colum I suggest that the simplest solution to foster innovation would be to revert to the pre-TCJA current year expensing for software development. Failure to revise these changes could potentially stifle software innovation, especially for startups and smaller companies that were previously incentivized by the ability to expense development costs in the current year.

New IRS R&E Rules Risk Stifling Software Innovation for Startups