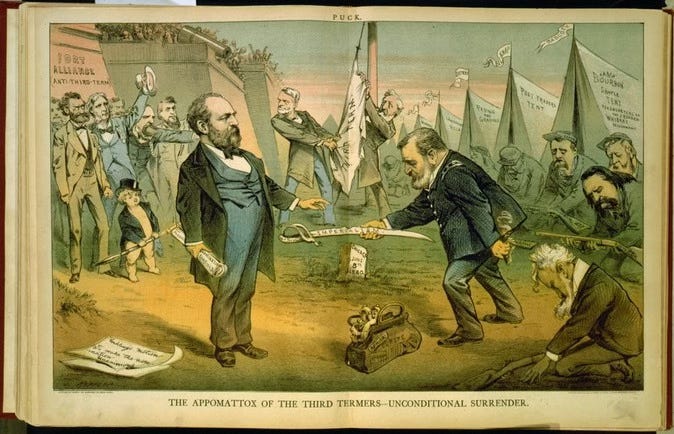

This Day in Legal History: 22nd Amendment to the US Constitution

On February 27, 1951, the 22nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, formally limiting the president to two terms in office. This amendment was a direct response to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s unprecedented four-term presidency, which spanned the Great Depression and World War II. Before Roosevelt, no president had served more than two terms, following the precedent set by George Washington. However, there was no constitutional restriction preventing a president from seeking additional terms.

Roosevelt’s long tenure raised concerns about excessive executive power and the potential for an elected leader to hold office indefinitely. After his death in 1945, Congress moved to ensure that no future president could serve more than two terms. The amendment was passed by Congress in 1947 and ratified by the required number of states in 1951. It states that no person may be elected president more than twice or serve more than ten years in cases where a vice president assumes the role due to a predecessor’s death or resignation.

Since its ratification, the 22nd Amendment has shaped U.S. presidential politics, preventing any leader from holding office for more than eight years. Some have argued that it protects democracy by preventing the concentration of power, while others believe it limits voter choice. Despite occasional calls for repeal, the amendment remains in effect, reinforcing the principle of regular transitions of power.

A federal court is scrutinizing the role of Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency (DGE) in cutting U.S. government spending, raising questions about transparency and legality. At a hearing, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly repeatedly pressed a Justice Department lawyer on Musk’s authority but received vague answers. Multiple lawsuits argue that DGE, which operates with secrecy, wields power beyond what is constitutionally allowed for agencies that require congressional approval or Senate confirmation.

Despite Musk’s public claims of leadership, the White House insists he is not an official DGE employee. Courts have been divided on the issue, with some judges refusing to block DGE’s actions due to a lack of clear evidence of immediate harm. However, Judge Jeannette Vargas temporarily restricted DGE’s access to Treasury Department systems over concerns about unauthorized data access.

The Trump administration’s shifting characterizations of DGE—sometimes calling it an agency, other times not—have further complicated legal battles. One judge described it as a “Goldilocks entity,” molded to fit legal needs. While some courts are hesitant to act without stronger evidence, ongoing lawsuits seek to bring DGE’s operations into clearer legal scrutiny.

'Where is Mr. Musk in all of this?' Judges question secrecy of DOGE's activities | Reuters

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case brought by Marlean Ames, a heterosexual woman who claims she was denied a promotion and later demoted due to her sexual orientation. Ames alleges that in 2019, her gay supervisor promoted a less qualified gay woman and replaced her with a gay man. The case challenges a legal standard that requires plaintiffs from majority groups—such as white or heterosexual individuals—to provide extra evidence of workplace discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Ames’ lawyer argued that Title VII protects all individuals from discrimination, not just historically marginalized groups. The state of Ohio, her former employer, countered that Ames had not proven bias, noting that decision-makers may not have even known her sexual orientation. Some justices expressed concern that ruling for Ames could flood the courts with discrimination claims. Others questioned whether the heightened standard for majority-group plaintiffs improperly excludes valid cases.

The case comes amid increasing lawsuits from white and straight workers alleging "reverse discrimination," as well as political pushback against diversity and inclusion programs. A ruling in Ames' favor could make it easier for majority-group plaintiffs to challenge employment decisions, potentially reshaping workplace discrimination law.

US Supreme Court hears straight woman's 'reverse' discrimination case | Reuters

President Donald Trump’s decision to designate Latin American drug cartels as terrorist organizations introduces new legal risks for U.S. businesses and migrants. The February 19 designation applies to groups like the Sinaloa Cartel and Tren de Aragua, allowing the Justice Department to prosecute cartel leaders for terrorism. However, legal experts warn that U.S. and foreign companies operating in cartel-controlled regions could also face prosecution if they make payments to these organizations, which could be considered material support for terrorism.

This concern is not hypothetical—similar cases have occurred before. In 2022, French cement company Lafarge pleaded guilty and paid $778 million in fines for making payments to terrorist-designated groups in Syria to keep its operations running. Given Mexico’s status as the U.S.’s largest trading partner, businesses must reassess their dealings in high-risk areas.

Beyond corporate liability, migrants who pay cartels for border crossings or send money to cartel-influenced regions could also be prosecuted. Additionally, drug-related offenses linked to designated cartels could carry harsher penalties, including a 20-year mandatory minimum sentence for narcoterrorism—double the usual drug trafficking penalty. The designation thus has sweeping implications for both corporate compliance and immigration enforcement.

Trump's terrorist label for cartels raises prosecution risks for companies | Reuters

In a piece I wrote for Forbes, I review the latest misguided foray into tech policy from the Trump administration. The White House has issued a memorandum condemning foreign digital services taxes (DSTs), arguing that they unfairly target American tech companies. The memo warns that unless these taxes are repealed, retaliatory tariffs will be imposed. However, this stance appears to protect Big Tech rather than uphold economic fairness, as these taxes exist to counter profit-shifting tactics that allow tech giants to avoid local taxation. The U.S. frequently applies its own extraterritorial laws, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the CLOUD Act, yet objects when other countries enforce similar policies on American firms.

The memorandum frames the issue as an attack on U.S. businesses, but every country has the right to tax corporations operating within its borders. DSTs primarily ensure that companies pay taxes where they generate revenue rather than in low-tax havens. The U.S. position ignores the broader global tax landscape and the rationale behind these policies, opting instead to shield Silicon Valley from accountability.

If the U.S. enacts tariffs in response, it could trigger a trade war that harms American farmers, manufacturers, and consumers while preserving Big Tech’s profits. The memorandum’s real purpose seems to be maintaining an uneven playing field where American firms operate abroad without the same obligations as local businesses.

Big Tech Protection: U.S. Picks A Trade Fight To Defend Tech Firms