This Day in Legal History: Fifteenth Amendment Ratified

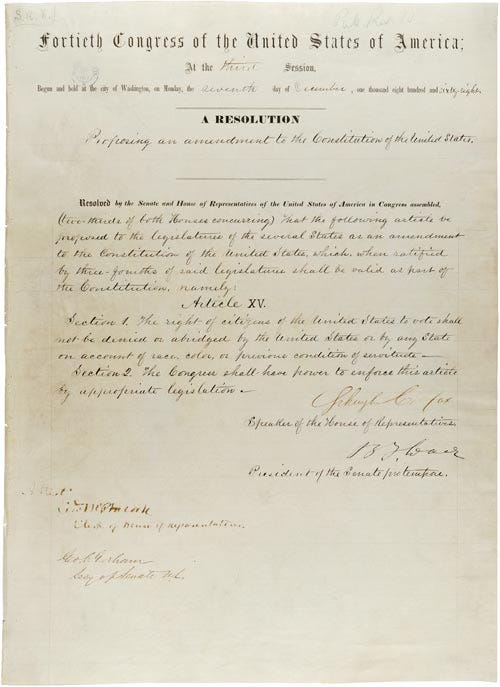

On February 3, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified, marking a pivotal moment in American legal history. The amendment prohibits federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Its ratification was the third and final of the Reconstruction Amendments, following the Thirteenth (abolishing slavery) and Fourteenth (guaranteeing equal protection and due process) Amendments.

The Fifteenth Amendment was a direct response to the systemic disenfranchisement of Black Americans in the post-Civil War South. While it granted a legal foundation for Black men’s suffrage, implementation faced immediate resistance. Southern states adopted literacy tests, poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and other discriminatory practices to circumvent the amendment and suppress Black political participation.

Despite its passage, the amendment’s guarantees would not be meaningfully enforced until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, nearly a century later. The legal battles stemming from the Fifteenth Amendment’s promise have shaped much of the country’s voting rights jurisprudence and continue to echo in current debates about voter ID laws, redistricting, and access to the ballot box.

A U.S. federal judge is set to hear arguments on February 5 regarding Danish company Ørsted’s request to lift the Trump administration’s pause on its offshore Sunrise Wind project near Long Island, New York. Ørsted has asked for a preliminary injunction, warning that without a decision by February 6, it could lose access to a specialized vessel crucial for cable installation, putting the project’s timeline, financial viability, and even survival at risk. The Interior Department halted five offshore wind projects in December, citing newly obtained, classified national security concerns, particularly radar interference. Ørsted’s filing states the company has already committed over $7 billion to the Sunrise Wind project, which is about 45% complete and projected to power nearly 600,000 homes by October.

Judge Royce Lamberth, who previously granted an injunction for Ørsted’s Revolution Wind project off Rhode Island, will preside over the case. Four similar wind developments have already won legal relief allowing construction to continue during litigation. The ongoing delays reflect broader tensions between offshore wind expansion and the Trump administration’s skepticism of the technology, as well as evolving security concerns.

US judge to consider last project challenge to Trump offshore wind pause | Reuters

The U.S. Department of Justice has launched a civil rights investigation into the fatal shooting of Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old ICU nurse, by federal immigration agents in Minneapolis. Pretti was killed during an enforcement operation that has since drawn national outrage and led the Trump administration to alter its tactics in Minnesota. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche said the FBI is conducting a preliminary review, with potential involvement from the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, though he emphasized that the investigation is still in early stages.

Video footage verified by Reuters shows Pretti being tackled by agents while holding a phone, and an officer retrieving a firearm from his body just before shots were fired. The Justice Department said a formal criminal civil rights probe would only proceed if the evidence supports it. Local officials have voiced distrust of the federal response and are conducting their own inquiry. Pretti is the second protester killed by federal agents in Minneapolis this month, and his family, represented by attorney Steve Schleicher, is demanding a transparent and impartial investigation. So far, no similar federal probe has been opened into the earlier shooting of Renee Good by an ICE officer.

US Justice Dept opens civil rights probe into Alex Pretti shooting, official says | Reuters

In this week’s column for Bloomberg Tax, I argue that Volkswagen’s decision to cancel plans for a new Audi plant in the U.S. highlights the limitations of using tariffs as a cornerstone of industrial policy. The assumption underpinning tariff-heavy strategies is that the U.S. market is irresistible enough to force global firms to onshore production, even as tariffs erode that market’s size and appeal. Tariffs have come to function like sin taxes—meant to discourage consumption—but unlike cigarettes or soda, the goal with trade policy is not abstention, but investment and economic engagement. Instead, firms like VW are responding by pulling back, as higher costs reduce consumer demand and make U.S. market share too small to justify large-scale investment. The belief that global manufacturers can swiftly build U.S. capacity ignores the time, cost, and uncertainty involved, especially in capital-intensive sectors. VW’s exit is rational: it doesn’t make financial sense to break ground on a multibillion-dollar plant when the target market is shrinking and returns are questionable.

Policymakers need to move beyond blunt tools and design trade incentives based on real market data, such as U.S. demand and potential return on investment. That means requiring ROI modeling before tariffs are imposed, and asking whether the targeted company has enough exposure to be moved by them. If the answer is no, we risk losing access to competitive products, jobs, and consumer choice—not gaining them. Trade policy should be surgical, not punitive, and should acknowledge that capital follows incentives, not threats.

In a piece I wrote for Forbes late last week, and with apologies for a double dose of me today: I examined California’s long-running flirtation with a mileage-based tax to replace its declining gas tax revenues—and how what began as a test program has quietly become a form of policymaking through delay. In 2014, the state authorized a pilot program to study a “road usage charge,” a per-mile fee designed to keep transportation funding solvent as gas consumption drops. That pilot wrapped up in 2017 and showed the system works: vehicles can be tracked, billing can be simulated, and the technical challenges are manageable. But nearly a decade later, no mileage tax has been implemented, and new legislation—AB 1421—would extend the advisory committee until 2035.

The real issue now isn’t feasibility but political avoidance. The state has drifted into a passive strategy where permanent pilots and advisory boards take the place of real decisions. This kind of inertia has a name: policy drift—when the law remains formally unchanged, but materially obsolete. California’s ongoing study phase has become a way to defer a difficult conversation about revenue and equity in a post-gasoline economy. The technology exists, and other states have already tested it. What’s missing is political will and public engagement.

AB 1421 doesn’t collect revenue or educate voters—it simply extends the status quo under the guise of preparation. From the outside, it looks like planning. In practice, it’s a weather balloon designed to measure political tolerance, not policy readiness.

California Mileage Tax—Pilot Programs And Permanent Policy Inertia