This Day in Legal History: Taft-Hartley Act

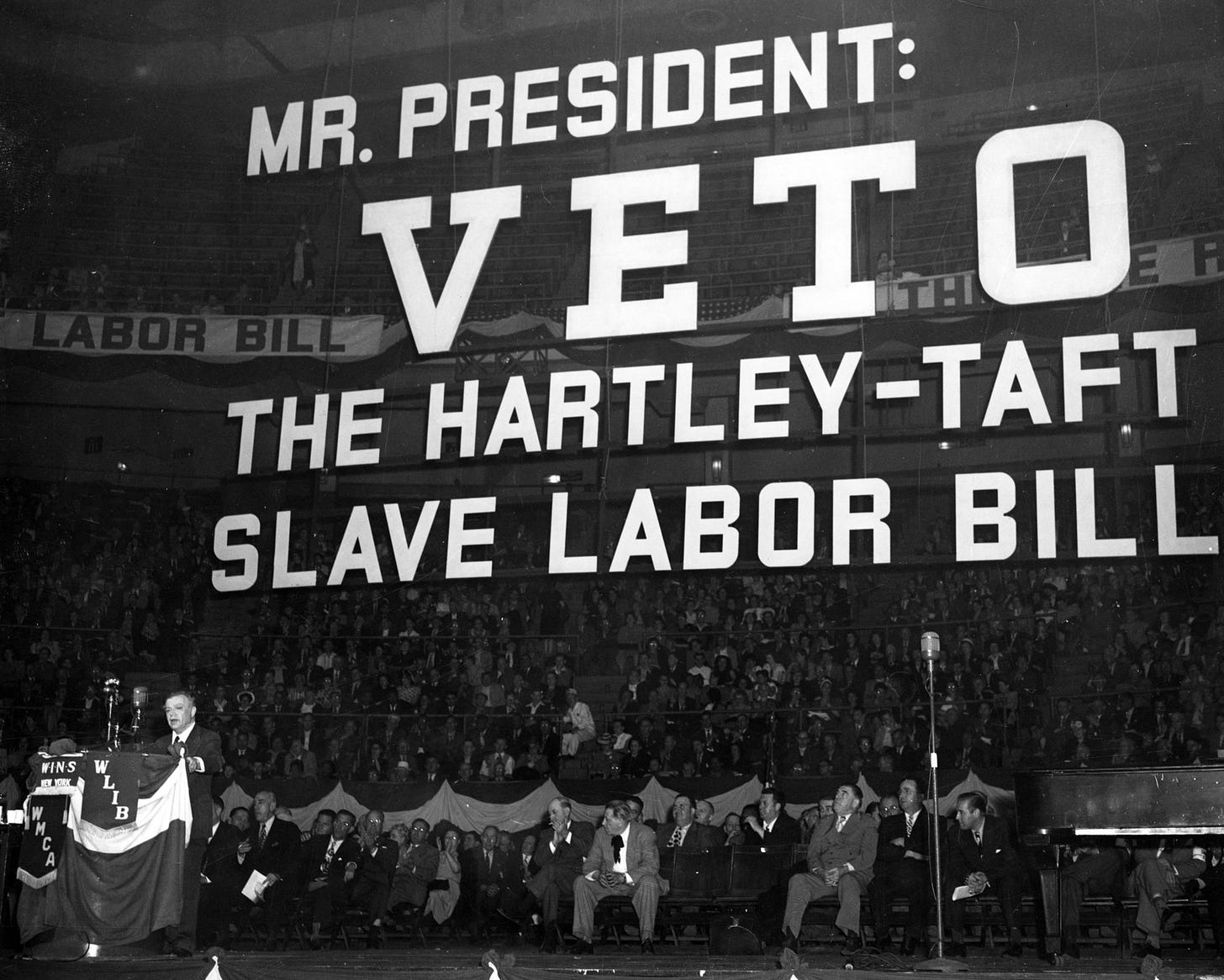

On June 23, 1947, the Labor-Management Relations Act—better known as the Taft-Hartley Act—became law after Congress overrode President Harry S. Truman’s veto. Sponsored by Senator Robert Taft and Representative Fred Hartley, the act was passed in response to growing concerns about union power and post-World War II labor strikes that disrupted the economy.

The law amended the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, which had established strong protections for labor organizing. Taft-Hartley introduced a series of restrictions on union activity, including prohibitions on secondary boycotts, jurisdictional strikes, and closed shops—arrangements where union membership is a condition of employment. It also allowed states to pass right-to-work laws, which prohibit union security agreements.

In a significant shift, the act required union leaders to sign affidavits affirming they were not members of the Communist Party, reflecting Cold War anxieties. It also authorized the president to intervene in strikes deemed a national emergency by imposing an 80-day cooling-off period.

Though labor leaders condemned the act as a betrayal of workers’ rights, and Truman called it a “slave-labor bill,” it marked a turning point in federal labor policy. The act curtailed union power and set the stage for decades of legal battles over labor practices. Its provisions remain influential in labor law to this day.

Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran national and Maryland resident, has been released on bail pending trial on federal migrant smuggling charges, according to a ruling issued Sunday by U.S. Magistrate Judge Barbara Holmes in Nashville. Although granted release, Abrego may still face immigration detention. He was deported to El Salvador in March despite a 2019 court ruling barring his removal due to risk of gang-related persecution—an action officials later admitted was an administrative error.

Abrego was brought back to the U.S. on June 6 after being indicted for allegedly coordinating a migrant smuggling operation involving over 100 border pickups and transporting drugs and firearms. He has pleaded not guilty, and his lawyers argue the charges are politically motivated, intended to obscure the Trump administration’s due process violations in his deportation.

Prosecutors rely on co-conspirators who are cooperating in exchange for leniency, which defense attorneys say undermines their credibility. In a separate case, a federal judge in Maryland is also investigating whether the Trump administration defied court orders in handling Abrego’s removal. The Supreme Court previously upheld the judge’s mandate to return him to the U.S.

Abrego Garcia ordered released pending trial on migrant smuggling charges | Reuters

A Republican-backed proposal to cap federal student loans for professional degrees is raising concerns among legal educators, who say it could disproportionately harm students attending lower-ranked law schools and those from minority or lower-income backgrounds. The bill, which passed the House and is now in the Senate, would limit annual borrowing to $50,000–$77,000 and cap total loans between $150,000 and $200,000. Currently, law students can borrow the full cost of tuition and living expenses.

The proposed caps would force students who exceed the limit to seek private loans, which often come with higher interest rates and stricter credit requirements. This could make legal education less accessible to students without co-signers or strong credit histories, particularly at schools with high tuition and lower job placement rates—factors that increase lending risk.

Experts warn that students at unranked or lower-ranked schools, which enroll higher percentages of minority and first-generation students, could be most affected. For example, Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School, which is unranked, reported a student body that was nearly 76% students of color, yet its graduates carry high debt compared to modest starting salaries.

Supporters of the cap argue that unlimited loans enable tuition inflation and poor returns on investment for taxpayers. Critics counter that the policy may reduce diversity in the legal profession and limit access to legal education for underrepresented groups.

Student loan caps could hit minorities, low-ranked law schools the hardest | Reuters

A piece I wrote for Forbes this week looks at Illinois’ reconsideration of a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) tax—an idea that failed to launch in 2019 but may be gaining traction again. With Illinois already levying one of the highest gas taxes in the nation, the state faces diminishing returns from fuel taxes as electric vehicles (EVs) proliferate and traditional cars become more efficient. Since road wear isn’t reduced by cleaner energy, and EVs are often heavier than gas-powered vehicles, the funding model needs to evolve.

The VMT tax offers a promising alternative: rather than taxing gallons of gas, it taxes the actual use of roads—miles driven—making it more of a user fee than a traditional tax. Ideally, it would be tiered based on vehicle weight, matching tax liability with pavement damage. Proposed legislation (SB1938) allows for variable pricing based on road type and time of day, which could introduce smart congestion pricing.

Concerns about surveillance have been raised, but the pilot program requires only minimal data, prohibits personal data collection, and provides GPS-free options. The program is temporary, must last at least a year, and will include a full review covering equity, logistics, data security, and fraud prevention.

Illinois has pushed the gas tax system as far as it can go and still faces infrastructure shortfalls. The VMT could represent not just a new tax, but a new way forward—fairer, more adaptable, and more sustainable. If Illinois gets it right, other states might follow.

Illinois Vehicle Mileage Tax—Fix The Roads And Fund The Future