This Day in Legal History: 25th Amendment

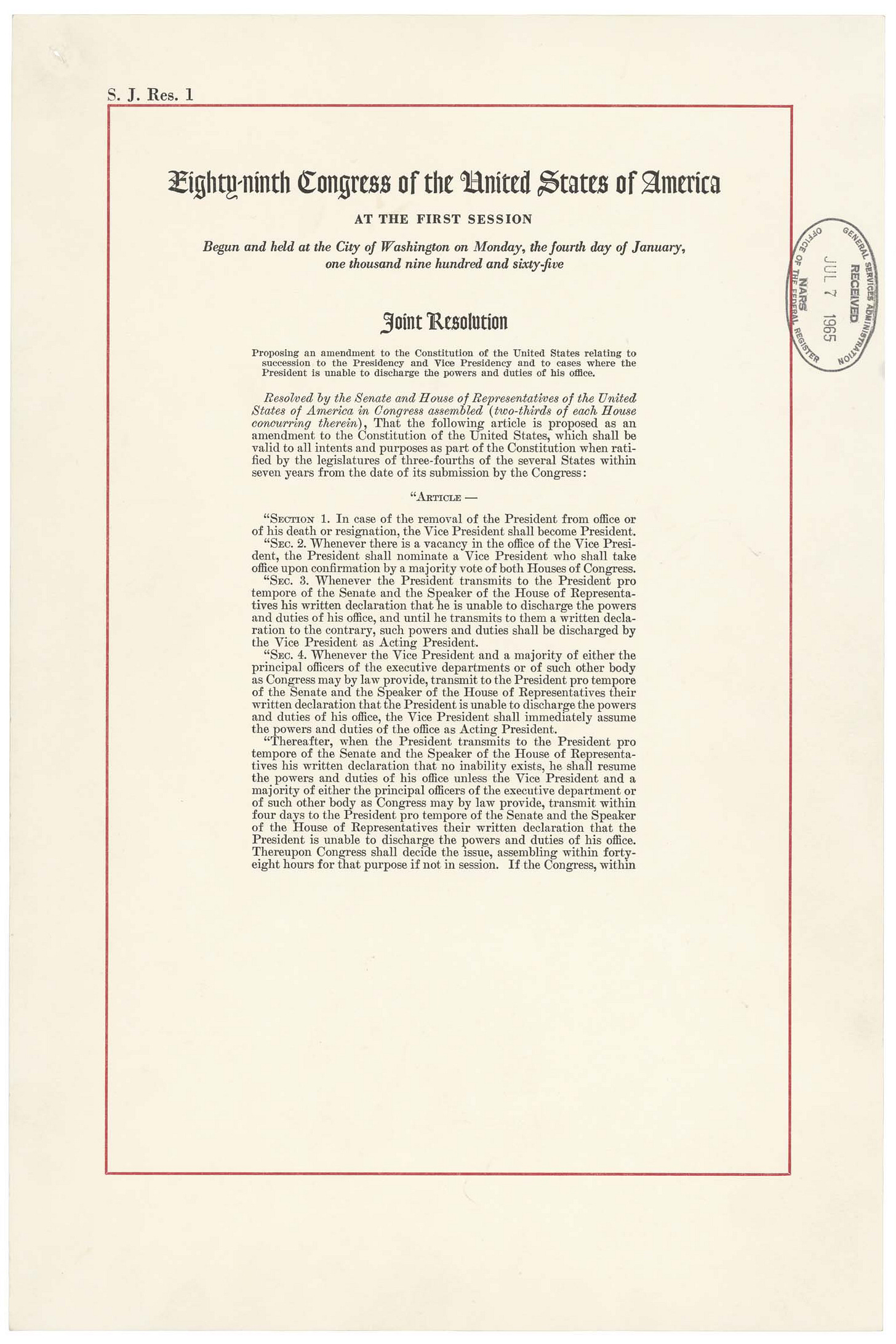

On February 10, 1967, the 25th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified, formally addressing presidential succession and disability for the first time in constitutional text. The need for such clarity had become urgent after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s repeated illnesses during his terms. Prior to this amendment, there was no definitive constitutional mechanism for filling a vacancy in the vice presidency or for managing presidential incapacity. The 25th Amendment established four key sections, each designed to ensure governmental stability during times of crisis.

Section 1 confirmed that if a president dies, resigns, or is removed, the vice president becomes president—not just acting president. Section 2 allowed for the appointment of a new vice president, with confirmation by both the House and Senate, in the event of a vacancy. This provision was put to use shortly after its ratification when Gerald Ford was appointed vice president in 1973 following Spiro Agnew’s resignation. Section 3 allowed a president to voluntarily transfer power to the vice president by submitting a written declaration to Congress—used during temporary medical procedures like surgeries.

Most controversial and significant is Section 4, which allows the vice president and a majority of the cabinet (or another body designated by Congress) to declare the president “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” This provision has never been fully invoked but has been a topic of discussion during times of perceived presidential instability. It establishes a legal mechanism for removing a president against their will, albeit temporarily, with congressional oversight. The amendment reflects a post-World War II concern for continuity of leadership in a nuclear age. Its ratification marks a critical evolution in constitutional law, ensuring the executive branch remains functional even under extraordinary circumstances.

A federal lawsuit filed in Texas alleges that an 18‑month‑old girl detained by U.S. immigration authorities was sent back into U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody after being hospitalized for a life‑threatening respiratory illness and then denied the medications doctors prescribed.

According to the filing, Amalia and her parents were held at the family detention center in Dilley, Texas after a routine immigration check‑in in December. The toddler became severely ill in January with extremely high fever and breathing problems, and a hospital diagnosed her with multiple serious infections including COVID‑19, pneumonia and RSV. After about 10 days in the hospital, she was discharged with a nebulizer, respiratory medication and nutritional supplements—but those were confiscated when she was returned to the detention facility.

The lawsuit says her parents repeatedly tried to obtain prescribed treatment from detention staff but were forced to wait in long lines and often were denied, contributing to the child’s health deterioration. Legal advocacy led to the family’s release after the emergency court filing; attorneys contend the case reflects broader problems with medical care, conditions and protections for children and families in immigration custody.

The Trump administration is proposing a significant change to federal employment law that would restrict fired federal workers from appealing their terminations to the independent Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). Under the plan, workers would instead have to appeal to the Office of Personnel Management (OPM)—a shift critics say would compromise impartiality, as the OPM director reports directly to the president.

The MSPB, historically tasked with mediating disputes between federal employees and agencies, experienced a 266% spike in appeals cases during Trump’s second term, likely due to a surge in federal job cuts. In 2025, the federal workforce shrank by 317,000 employees, though OPM claims most departures were voluntary through buyouts rather than firings—an assertion not independently verified.

This latest proposal would further President Trump’s second-term agenda to reduce the size of the federal workforce while also narrowing employees’ legal options for challenging dismissals. Trump has also weakened job protection enforcement by removing officials from agencies that safeguard civil service rights. Critics argue the proposal consolidates power over personnel disputes within the executive branch, potentially eroding longstanding civil service protections.

Trump seeks to limit legal options for fired federal workers | Reuters

My column for Bloomberg Tax this week is about tax holidays for data centers–or the folly in offering them. India’s bold new play to become the backbone of global digital infrastructure isn’t just about its headline-grabbing 20-year tax holiday for data centers. The real shift is happening in the fine print—a 15% safe harbor for transfer pricing that removes much of the risk multinationals face when operating across borders. If a company like Microsoft India applies a simple 15% markup on services sold to its U.S. parent, the Indian government agrees not to challenge the pricing. That’s not just a tax break—it’s operational certainty, and it makes India’s offer much more attractive than anything U.S. states currently have on the table.

In contrast, American states are still offering scattered subsidies—property tax breaks, zoning perks, utility discounts—without any unified vision or reliable regulatory structure. There’s no equivalent to India’s safe harbor. No clarity on transfer pricing. No coordination across state lines. The result is what I see as economic development policy by improv, where officials hand out incentives like they’re bidding on a sports arena rather than negotiating infrastructure strategy.

And what do U.S. taxpayers get in return? A burst of construction, a few permanent jobs, and a long-term commitment to expensive infrastructure upgrades for data centers that don’t meaningfully plug into the local economy. Meanwhile, India is making an offer that fits squarely onto a multinational’s balance sheet—pre-agreed pricing, national alignment, and a clear path to long-term cost savings.

I don’t think the solution is to try to beat India at its own game. But if states are going to offer incentives, they need to extract something real in return: energy infrastructure, broadband expansion, or compute resources that benefit the public. Otherwise, they’re just footing the bill for someone else’s global expansion.