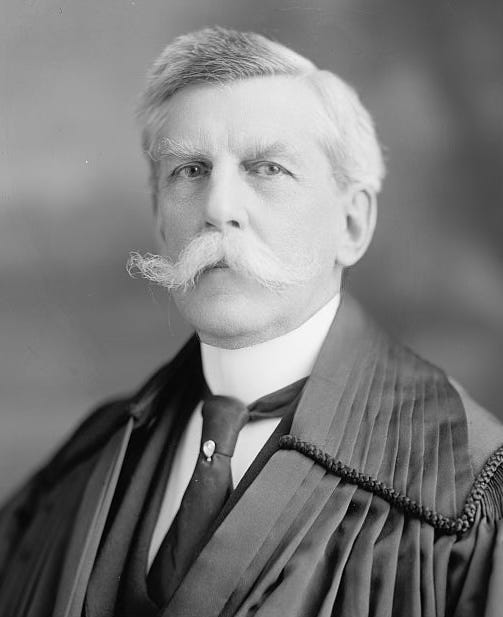

This Day in Legal History: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr’s Kid Sworn in as Justice

On December 8, 1902, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was sworn in as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, beginning one of the most storied judicial careers in American history. Appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt, Holmes brought not just legal brilliance but a fierce sense of independence to the bench—qualities that would define his nearly 30-year tenure. He would become known as “The Great Dissenter,” not because he loved conflict, but because he saw the Constitution as a living document that demanded humility, skepticism of dogma, and above all, respect for democratic governance.

Holmes shaped modern constitutional law, particularly in his groundbreaking First Amendment opinions. In Schenck v. United States (1919), he famously coined the “clear and present danger” test, establishing a foundational limit on government power to suppress speech. Though that decision upheld a conviction, Holmes’s dissent later that year in Abrams v. United States marked his turn toward a much broader vision of free expression—one that laid the groundwork for modern civil liberties jurisprudence.

A Civil War veteran wounded at Antietam, Holmes served with the Massachusetts Volunteers and carried shrapnel in his body for the rest of his life. His long memory gave him historical depth: legend holds he met both Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy—Lincoln as a young Union officer in Washington, and JFK decades later when the future president visited the aged Holmes on his 90th birthday. While the Lincoln meeting is plausible and widely accepted, the Kennedy encounter is well documented—photos exist of JFK visiting Holmes in 1932, shortly before the justice’s death.

Holmes’s legal philosophy emphasized restraint, often reminding fellow jurists that the Constitution “is made for people of fundamentally differing views.” He resisted turning the judiciary into a super-legislature, warning against confusing personal preference with constitutional mandate. His opinions, dissents, and aphorisms—“taxes are what we pay for civilized society,” among them—still echo in courtrooms and classrooms today.

By the time he retired in 1932 at age 90, Holmes had become an icon: not just a jurist, but a symbol of intellectual honesty and constitutional humility. His December 8 appointment wasn’t just another judicial swearing-in—it was the beginning of a philosophical legacy that still defines the boundaries of American legal thought.

Amit Agarwal, a former clerk to Justices Alito and Kavanaugh, will soon find himself arguing against the very ideology he once clerked under—defending limits on presidential power in a case that could gut a nearly century-old precedent, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935). He’ll be representing former FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter, who sued after President Trump gave her the boot, and whose case now tees up a potentially seismic shift in how presidents control independent agencies.

At issue is whether the president can remove members of independent commissions—like the FTC—at will, or whether statutory “for cause” protections, created by Congress and upheld since the New Deal, still mean anything. If the Supreme Court overturns Humphrey’s Executor, it would blow a hole in the legal framework that has shielded multi-member agencies from raw political interference since Roosevelt tried—and failed—to remake the FTC in his own image.

Let’s pause here: Humphrey’s Executor isn’t just some dusty New Deal relic. It drew a sharp line between executive officers who serve the president directly and independent regulators who are supposed to be immune from daily political whims. The Court in 1935 said: no, FDR, you can’t just fire an FTC commissioner because he’s not singing from your hymnbook. That ruling became the backbone of modern agency independence—from the Fed to the SEC to the NLRB. Without it, the next president could dismiss any regulatory head who doesn’t toe the party line. You want crypto rules to mean something? Food safety? Banking supervision? Say goodbye to all that if we pretend these agencies are just White House interns with better titles.

But here’s where it gets interesting: Agarwal is making the conservative case for restraint. Now working at Protect Democracy, he’s arguing that letting presidents fire independent commissioners at will isn’t a win for constitutional governance—it’s a power grab that warps the original design. He’s invoked Burkean conservatism—the idea that practical experience should trump theoretical purity—and warns that blind devotion to the “unitary executive theory” threatens institutional integrity more than it protects separation of powers.

And Agarwal isn’t alone. A collection of conservative legal scholars, former judges, and ex-White House lawyers—some with deep Federalist Society credentials—have filed briefs supporting his position. Their argument? That Humphrey’s Executor is an “originalist” decision, faithful to the Founders’ ambivalence about concentrated executive power, especially in domestic administration.

Still, let’s be honest: the Court is unlikely to be swayed by this internal dissent. The Roberts Court has already chipped away at agency independence in decisions like Seila Law (2020) and Loper Bright (2024), where it let Trump fire the CFPB director and overturned Chevron deference respectively. With a solid conservative majority, and multiple justices openly embracing a muscular vision of presidential control, the writing may already be on the wall.

Which is precisely what makes Agarwal’s stand so notable. This isn’t some progressive legal activist parachuting in from the ACLU (though his wife did work there). This is someone who backed Kavanaugh publicly, donated to Nikki Haley, and spent years rising through the conservative legal pipeline—only to conclude that this version of executive power isn’t conservative at all. It’s reactionary.

So what happens if Humphrey’s goes down? Beyond the short-term question of whether Slaughter gets her job back, the bigger issue is how much power presidents will wield over what were supposed to be politically insulated regulatory bodies. Will a ruling in Trump’s favor mean future presidents can purge the Fed board? Fire NLRB members mid-term? Flatten the independence of enforcement agencies? The Court may claim it’s just restoring “constitutional structure,” but don’t be surprised if that structure starts to look a lot like one-man rule.

Agarwal, to his credit, is saying: not so fast. Sometimes conserving means preserving. And sometimes defending the Constitution means restraining the people who claim to speak for it the loudest.

Ex-Alito, Kavanaugh Clerk Defends Limits on Trump’s Firing Power

Fight over Trump’s power to fire FTC member heads to US Supreme Court | Reuters

A federal judge has temporarily barred the Justice Department from using evidence seized from Daniel Richman, a former legal adviser to ex-FBI Director James Comey, in any future attempts to revive criminal charges against Comey. The move comes just weeks after the original case was dismissed due to the lead prosecutor’s unlawful appointment.

At issue is whether federal prosecutors violated Richman’s Fourth Amendment rights by searching his personal computer without a warrant during earlier investigations into media leaks tied to Comey’s 2020 congressional testimony. U.S. District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly sided with Richman—for now—saying he’s likely to succeed on the merits and ordering the government to isolate and secure the data until at least December 12.

The contested materials had been used to support now-dropped charges that Comey made false statements and obstructed Congress regarding FBI leaks about the Clinton and Trump investigations. But Richman, once a special FBI employee himself, argues the search was illegal and wants the files deleted or returned.

The Justice Department, undeterred, is reportedly considering a second indictment of Comey. But between shaky prosecutorial appointments and constitutional challenges like this one, their case is rapidly sliding into legally questionable territory.

US federal judge temporarily blocks evidence use in dismissed Comey case | Reuters

The U.S. Supreme Court has declined to review a controversial book removal case out of Llano County, Texas, effectively allowing local officials to keep 17 books off public library shelves—titles that deal with race, LGBTQ+ identity, puberty, and even flatulence.

The justices let stand a divided 5th Circuit ruling that found no First Amendment violation in the county’s decision to pull the books. That decision reversed a lower court order requiring the books be returned and rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that library patrons have a constitutional “right to receive information.” The 5th Circuit held that libraries have wide discretion to curate collections, and that removing titles doesn’t equate to banning them altogether—people can still buy them online, the court reasoned.

The dispute began in 2021 when local officials responded to complaints by residents, ultimately purging books including Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen (due to nude illustrations), as well as works on slavery and gender identity. Opponents of the removal sued, citing free speech violations. But the case now stands as a significant blow to that theory—at least in the 5th Circuit, which covers Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

The Supreme Court’s refusal to intervene leaves unresolved a key question: does the First Amendment protect not just the right to speak, but the right to access certain information in public institutions? For now, in parts of the South, the answer appears to be no.

US Supreme Court turns away appeal of Texas library book ban | Reuters