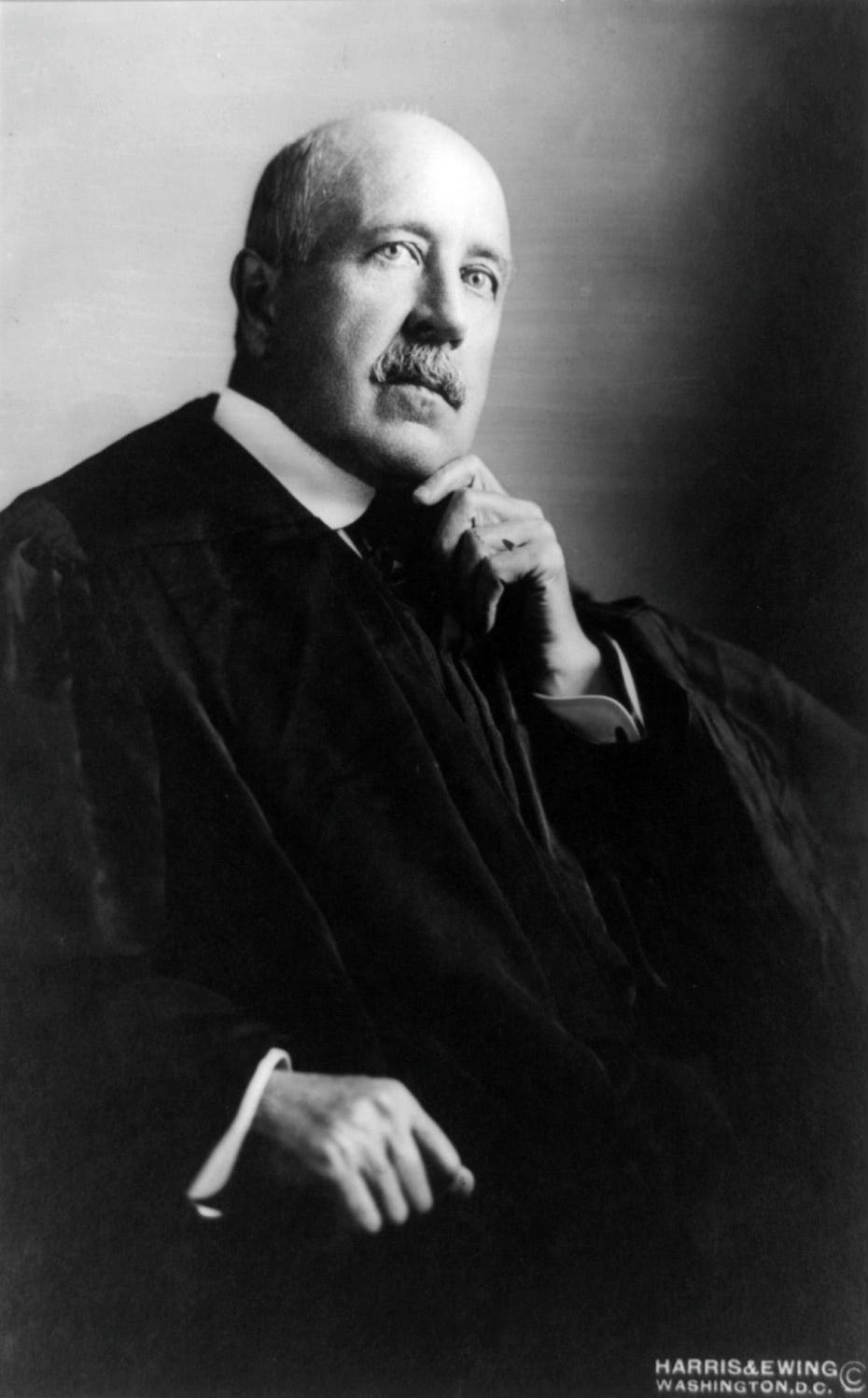

This Day in Legal History: Judge Robert W. Archbald Impeached

On January 13, 1913, Judge Robert W. Archbald of the U.S. Commerce Court was convicted by the U.S. Senate on articles of impeachment and removed from office, becoming one of the earliest federal judges ousted through this constitutional process. The House had impeached him the prior July on thirteen charges of corruption and misconduct, five of which the Senate upheld. Archbald had used his judicial position to secure favorable deals from railroads and coal companies—entities that regularly appeared before his court. These secretive contracts, executed through intermediaries to obscure his involvement, allowed him to purchase valuable coal lands below market value.

One of the more egregious acts involved advising a railroad representative on how to amend legal pleadings to improve their chances of winning in court—a direct violation of judicial ethics. After a twenty-eight-year judicial career, Archbald’s fall was swift. His defense largely relied on claims of pure motives, rather than denial of the facts. A senator observed afterward that Archbald was “convicted, not so much of being corrupt, as of lack of plain common sense,” noting his failure to grasp the ethical boundaries expected of judges.

The Senate vote was overwhelming, with only five senators dissenting. Every former judge in the Senate, save one, voted to convict. Archbald’s conviction marked the first successful impeachment for judicial corruption in U.S. history; earlier impeachments, like that of Judge Pickering in 1804, were rooted in issues like insanity, not unethical conduct. The case prompted calls for reform of the impeachment process itself, with suggestions to create a special judicial conduct court or authorize Senate committees to streamline trials. More broadly, the case had a chilling effect throughout public service, reinforcing ethical standards across all levels of government.

Uber is facing a high-stakes sexual assault trial in Phoenix that could have sweeping implications for thousands of similar lawsuits. The case, brought by Oklahoma resident Jaylynn Dean, alleges that Uber failed to protect her from an assault by a driver in 2023. Dean claims Uber has long been aware of sexual assaults committed by drivers but has not taken adequate steps to improve rider safety. This trial marks the first federal bellwether case in a massive consolidation of over 3,000 lawsuits involving similar allegations.

Uber maintains that it should not be held liable for criminal actions of independent contractors, arguing its safety features, background checks, and transparency are sufficient. Still, the company faces additional lawsuits in California state court and has been criticized for its historic lack of oversight and a culture focused more on growth than safety.

A jury in a previous California case found Uber negligent but ruled that negligence wasn’t a direct cause of harm. Uber tried to delay Dean’s trial, claiming her attorneys influenced the jury pool with misleading advertisements, but the judge allowed proceedings to continue. The outcome could influence settlement talks, regulatory scrutiny, and investor confidence as Uber continues to defend its safety record.

Uber faces sexual assault trial in Arizona that puts its safety record under scrutiny | Reuters

The U.S. Supreme Court is set to hear arguments in two high-profile cases challenging state laws in Idaho and West Virginia that bar transgender students from participating in female sports teams. While the court previously upheld a ban on gender-affirming care for minors in Tennessee, that ruling was seen as narrow. The decision to now consider sports-related bans has heightened concerns among transgender rights advocates about broader implications for legal protections.

At the heart of these cases is whether such bans violate the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause or Title IX, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in education. Legal scholars warn that the court’s ruling could shape future policies affecting transgender people beyond athletics—such as bathroom access, military service, and healthcare. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has previously supported limits on transgender rights, including allowing restrictions on gender markers for passports and banning transgender people from military service.

Idaho’s law is being challenged by Lindsay Hecox, a transgender college student who has since stopped playing sports, while West Virginia’s ban is being challenged by 15-year-old Becky Pepper-Jackson, who has been allowed to compete under lower court rulings. The states argue the laws protect fairness in women’s sports by preventing perceived competitive advantages. Lower courts have reached opposing conclusions on the legality of the bans, setting the stage for the Supreme Court to clarify whether restrictions based on biological sex or transgender status require heightened scrutiny.

The Court may also have to decide whether its 2020 decision protecting transgender workers under Title VII extends to school settings under Title IX. Legal observers say this case could reshape how courts approach not just transgender rights but broader equal protection claims.

US Supreme Court’s next transgender rights battle could affect more than sports | Reuters

The U.S. Supreme Court has declined to hear Citigroup’s appeal in a lawsuit accusing the bank of enabling a major fraud at Mexican oil services company Oceanografía, effectively allowing the case to proceed. More than 30 plaintiffs—including bondholders, shipping firms, and Rabobank—allege that Citigroup’s Banamex unit knowingly financed Oceanografía to the tune of $3.3 billion between 2008 and 2014, despite the company’s mounting debt and fraudulent practices, including forged Pemex signatures.

Oceanografía, which serviced Mexico’s state-owned oil giant Pemex, collapsed in 2014 and was later declared bankrupt. Citigroup uncovered $430 million in fraudulent advances and was fined $4.75 million by the SEC in 2018 for inadequate internal controls. Plaintiffs argue Citigroup hid critical information while profiting from interest on the advances.

At the center of the legal battle is whether bondholders can sue Citigroup under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), which allows for triple damages. Citigroup contended their claims were standard securities fraud allegations not suited for RICO and pointed to conflicting rulings in other federal appeals courts. However, the 11th Circuit found the plaintiffs’ claims plausible, noting it defied belief that a sophisticated bank like Citigroup was unaware of the fraud. By refusing to hear the appeal, the Supreme Court leaves that ruling intact and allows the lawsuit to move forward.

US Supreme Court rebuffs Citigroup appeal in lawsuit over Mexican oil company fraud | Reuters

This week, my column for Bloomberg looks at an obscure but telling tax provision: the so-called NASCAR tax break.

Dozens of tax provisions expired at the end of 2025, and Congress will soon debate whether to revive them. Among these is the motorsports entertainment complex depreciation break, which allows racetrack owners to write off their facilities over just seven years—a timeline far shorter than that allowed for buildings like housing or wastewater plants. Initially enacted in 2004 as part of the American Jobs Creation Act, the break was a reaction to a Treasury reclassification effort that would have extended depreciation timelines for motorsports. Rather than accepting the change, Congress locked in the favorable treatment to preserve the status quo.

Since then, the provision has been extended repeatedly, despite no clear policy rationale or economic justification. Unlike other tax incentives that at least attempt to stimulate broader economic development, the NASCAR break benefits a narrow group of wealthy owners in a lucrative, sponsor-heavy industry. The economic spillover is minimal, and unlike subsidies for sports stadiums—which are themselves of dubious value—this break doesn’t even offer the illusion of local benefit.

Its survival has more to do with inertia and lobbying than public interest. Letting it remain expired would save money and demonstrate that the tax code isn’t permanently rigged in favor of politically connected sectors. More broadly, the column argues for a disciplined framework to evaluate all expiring provisions based on economic efficiency, equity, administrability, and demonstrated value.